Bill Dentzer

Writer / Journalist

A veteran political journalist based in Washington D.C., Bill Dentzer reported on local and state government in New York early in his career, then from 2014 covered statehouses in Idaho, Utah and the important swing state of Nevada for daily news outlets. In between he held communications roles in government, financial and professional services, and media.

(Image: From steps of Lincoln Memorial, August 2023)

ABOUT

IN BRIEF

Veteran reporter, 20+ years of experience reporting on federal, state and local government and politics. Positions held in New York, Idaho, Utah, and Nevada. Now based in Washington, D.C.

GET CVSKILLS

Government & politics • Elections & campaigns • Enterprise & investigations • Data journalism • Photography & videographyStatehouse reporting

Data processing/analysis (Python, web scraping, AI)

Photo/video/graphics production and editing

Web content/publishing/development, Wordpress

Statehouse reporting

Data processing/analysis (Python, web scraping, AI)

Photo/video/graphics production and editing

Web content/publishing/development, Wordpress

POSITIONS HELD

2018-2022

LAS VEGAS REVIEW-JOURNAL

CAPITOL BUREAU REPORTER

Covered legislature, governor and executive branch, state and federal judiciary, and major/breaking regional news (California and northern Nevada). Clips

2017-2018

SALT LAKE TRIBUNE

GOVERNMENT REPORTER

Covered Salt Lake City (primary), county, and state government and politics. Clips

2014-2017

IDAHO STATESMAN

STATEHOUSE REPORTER

Covered legislature, governor and executive branch, federal officeholders. Analyst/panelist on PBS-affiliate news program and campaign debates. Clips

FEATURED

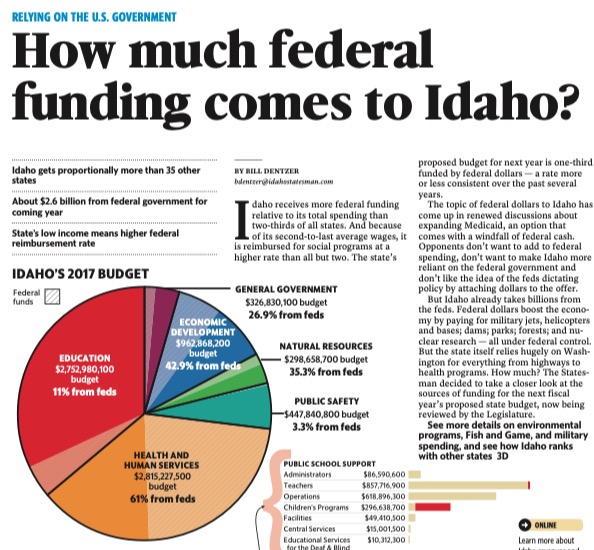

TAKE THE MONEY AND FUND

#DATA REPORTING

Idaho lawmakers resisted expanding Medicaid on grounds that they don’t want to make Idaho more reliant on the federal government or have the feds dictate policy. But Idaho already takes billions from Washington. More than one-third of all state spending is federally funded, higher than average for all states and 15th overall. Article

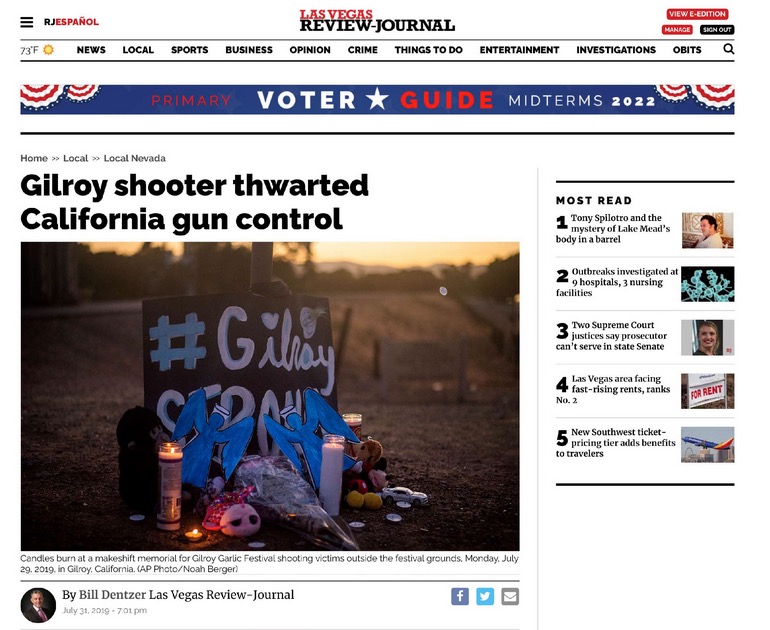

SHOOTER ELUDED CA GUN LAWS

A man who killed three in California had only to drive to Nevada to legally buy the gun he used.

View StorySHOOTER ELUDED CA GUN LAWS

#INVESTIGATION

The semiautomatic rifle a shooter used to kill three people in Gilroy, Calif., is banned for sale in that state. It lists for $700 at a Fallon, Nev., gun dealer where the man legally bought the weapon over the internet. Article

MONSTER SESSION WRAP-UP

The longest story ever published online at the RJ, and among our most visited links, was our wrap-up of the 2019 legislative session.

View StoryMONSTER SESSION WRAP-UP

#BEAT REPORTING

The longest story ever published online at the Review-Journal ran in two parts in the print edition. A functional session reference, it was among the most visited news story pages ever. Article

THE TALK OF STOREY COUNTY

A sheriff with a checkered past and present keeps winning election in spite of it.

View StoryTHE TALK OF STOREY COUNTY

#INVESTIGATION

The embattled sheriff of a rural Nevada keeps winning re-election amid charges of workplace sexual harassment and discrimination, allegations of sexual crimes, and three confirmed state ethics violations. Article

LAND GRAB IN SLC

State lawmakers rolled right over the city’s plans for thousands of acres in its undeveloped northwest.

View StoryLAND GRAB IN SLC

#BEAT REPORTING #ENTERPRISE

As the 2018 legislative session rushed to a close, leadership of the GOP-controlled body engineered a modern-day land grab to wrest control of a lucrative economic development plan from Democrats in Salt Lake City. Article

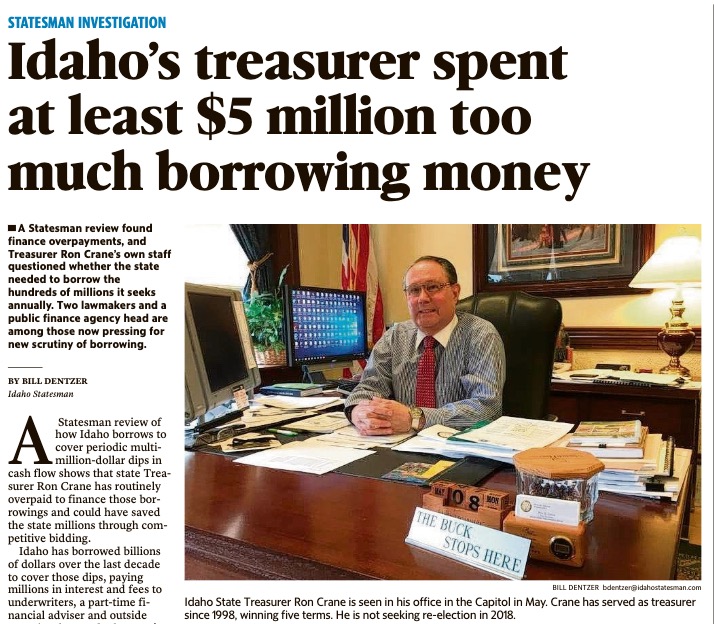

STATE WASTES MILLIONS ON BORROWINGS

Idaho wasted millions of dollars borrowing more than it needed and forgoing competitive bidding.

View StorySTATE WASTES MILLIONS ON BORROWINGS

#INVESTIGATION

A review of the costs of issuing debt in Idaho showed the longtime state treasurer’s practices wasted millions of public dollars financing the borrowings. Article

FAITHFUL PRAY, CHILDREN DIE?

Religious freedom collides with the state's laws on keeping children safe.

View StoryFAITHFUL PRAY, CHILDREN DIE?

#ENTERPRISE

Idaho’s faith-healing exemption removed penalties for withholding medical assistance in cases where a parent or guardian “chooses for his child treatment by prayer or spiritual means alone.” Lawmakers face the the question of whether First Amendment religious freedoms protect the faithful at the cost of protecting children. Article

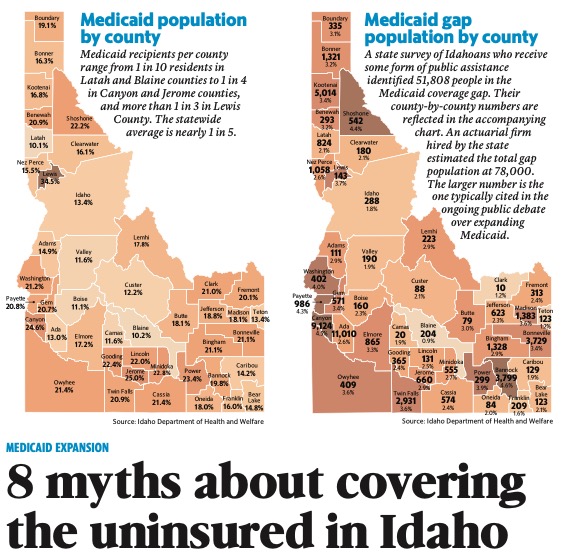

EIGHT MYTHS ABOUT MEDICAID

#BEAT REPORTING

Idaho dragged its heels on expanding Medicaid coverage as provide for under Obamacare. Opposition to doing it was built on a raft of faulty or flat out wrong assumptions. Article

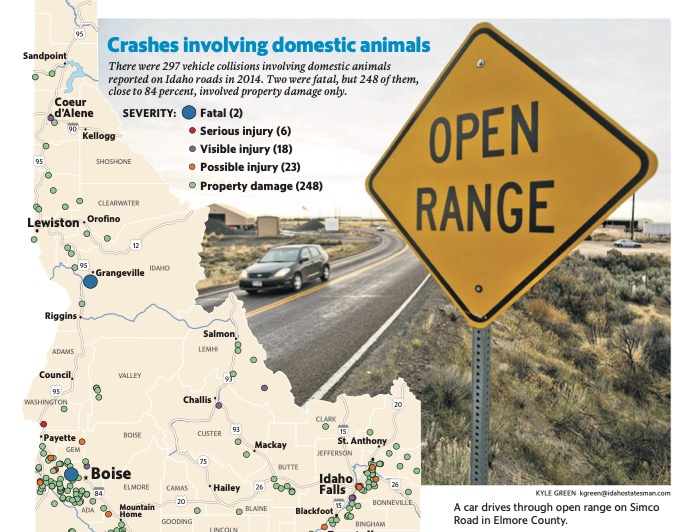

DON’T FENCE ME IN

Open range laws in Western states favor livestock owners, hold motorists liable.

View StoryDON’T FENCE ME IN

#ENTERPRISE

Those unlucky enough to collide with livestock in the open range are financially liable not only for their injuries and damage to their vehicles, but also for the animal they strike. In Idaho and other Western states, as traditional land uses cede ground to development and people, not everyone thinks that’s a fair deal. Article

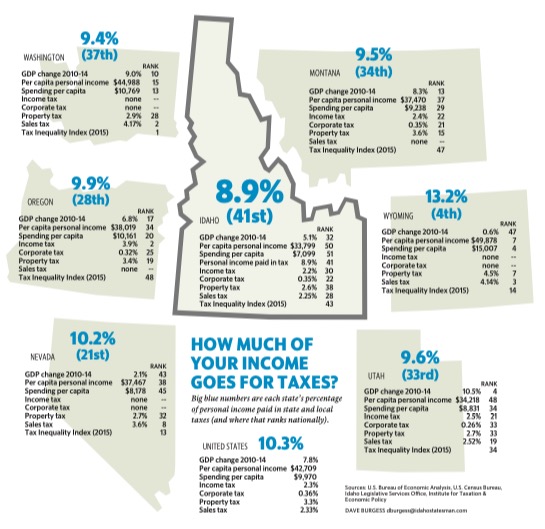

IDAHO TAXES LOWER THAN MOST STATES

Idaho's tax burden is light – and fair – compared to nearby states.

View StoryIDAHO TAXES LOWER THAN MOST STATES

#BEAT REPORTING #DATA REPORTING

Idaho Republicans always want to cut state taxes. But the state’s taxes are already lower, and fairer, than most other states. The state spends less per capita on its residents than any state in the nation. And its stingy spending matches its overall tax burden: it ranks 41st in taxes paid as a percentage of personal income. Article

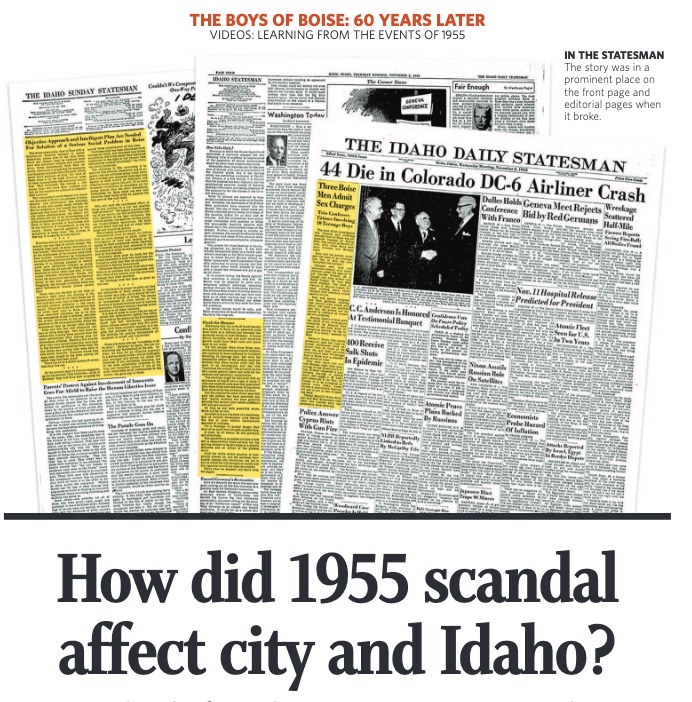

60 YEARS AFTER, THE BOYS OF BOISE

A 1950s witch hunt targeted gay men in Boise. It still haunts the city.

View Story60 YEARS AFTER, THE BOYS OF BOISE

#ENTERPRISE

In 1955, a county probation officer arrested three men for “immoral acts involving teenage boys.” In McCarthyesque fashion, he alleged hundreds more incidents. Eventually 16 men would be charged in a witch hunt that, decades later, still makes Boiseans squirm. Article

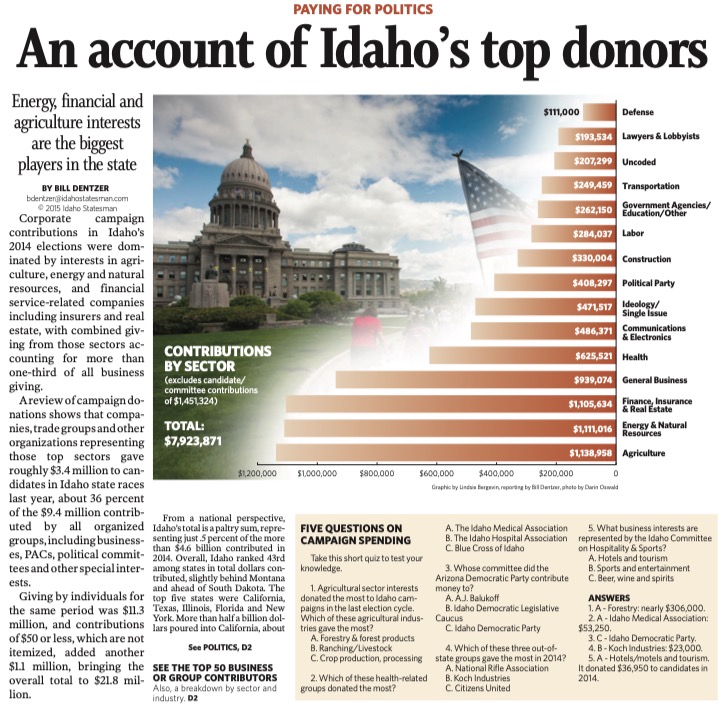

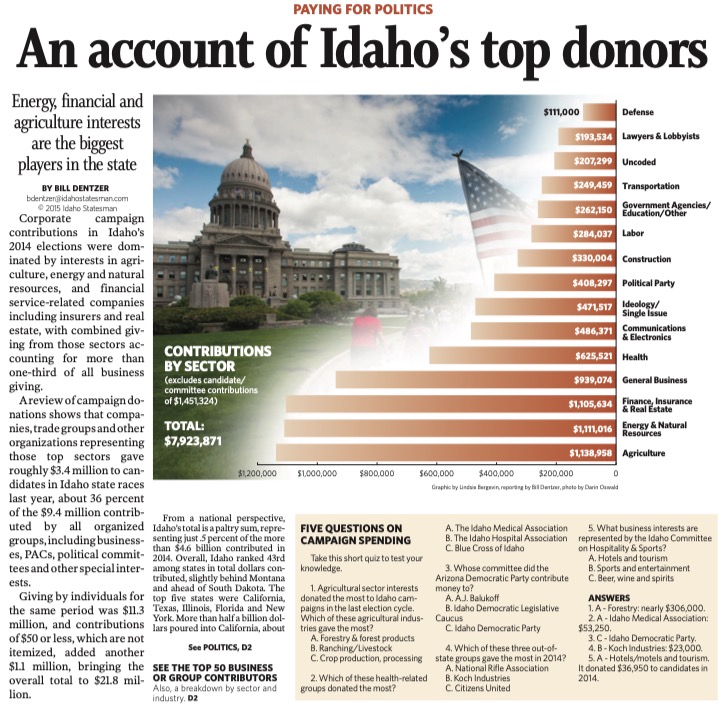

BIGGEST CORPORATE CONTRIBUTORS

Who are the deep-pocketed corporate patrons contributing to Idaho candidates for office.

View StoryBIGGEST CORPORATE CONTRIBUTORS

#DATA REPORTING

The top corporate contributors to Idaho elections might just be who you thought they’d be in an mostly rural agricultural state with vast natural resources. Article

MORE WRITING

Candidate denies racist text

On Martin Luther King Jr. Day, an unapologetically left-leaning blogger posted a screenshot of a […]

Virginia result for Nevada? Not so fast

Could Nevada voters in 2022 follow Virginia’s lead Tuesday, electing Republicans in statewide races next […]

Redistricting: What you should know

What redistricting means for Nevada, how it’s done, and why you might care. Website link […]

Gov preps for re-election bid

The first-term governor looks ahead to a race that will surf pent-up voter reaction to […]

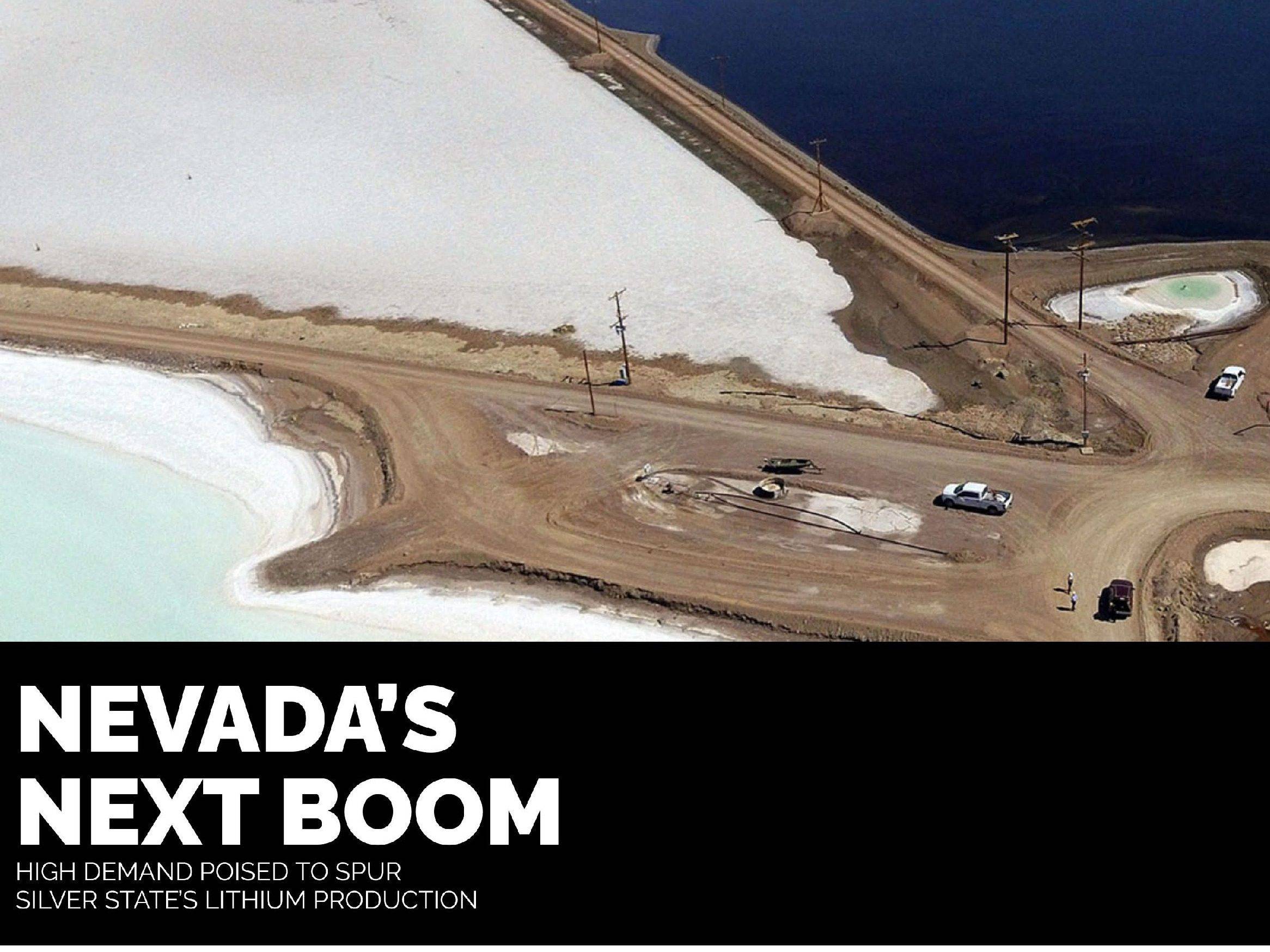

Nevada’s next boom? Enter lithium

With global demand for cleaner energy to power cars, smart homes and phones predicted to […]

Former sheriff accused in abduction

A former county sheriff got caught up in a Reno man’s attempt to abscond with […]

First female majority in U.S.

Nevada’s 2019 Legislature was the first in the nation to have a female majority, and […]

Sheriff keeps job despite complaints

An embattled sheriff in rural Nevada keeps winning re-election amid charges of workplace sexual harassment […]

2018 elections show Nevada in blue column

Democrats cleaned up in Nevada’s midterm elections as the state continued its move into solid […]

Utah GOP power grab from SLC Dems

The Legislature rolled right over the city’s plans for thousand of acres in its undeveloped […]

Treasurer misspent on borrowings

A look at the costs of issuing debt in Idaho showed the longtime state treasurer’s […]

Religion freedom or medical neglect?

Idaho has faith-healing exemptions in state child protection laws that exonerate caregivers who decline medical […]

Open range laws are ag-friendly

Open range laws mean if you hit a cow on the road, you’re liable not […]

Sun-Stopping

21 December From the Latin sol, for sun, and sistere, to stand still, comes solstice […]

Mustering In

Tiny Cressona nestles in the Appalachian coal country of southeastern Pennsylvania, about 130 miles […]

Site designed/developed by Bill Dentzer. Copyright © 2023 Bill Dentzer. All Rights Reserved. Former Site